Dozing and waking to the earth-shaking roar of unmuffled car and truck engines, I heard the sound I hate the most in the world: the whiny, pointless gurgling of motorbikes. There were loud conversations, hawkers, car horns, barking dogs. I leaned out of bed to check the time: 07:40. "Six more days of this? I will be exhausted!" I thought, wondering if I had made a mistake in coming to such a noisy place. The infernal din was soon augmented by the sound of drills and hammers.

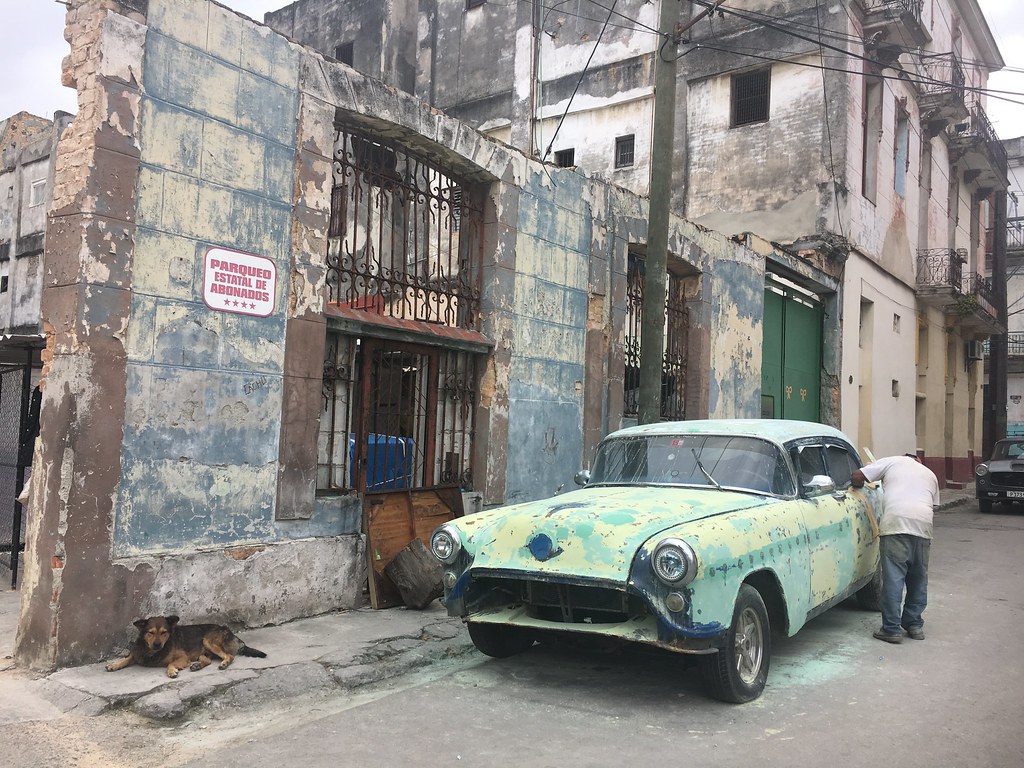

I walked from my bedroom through my private lounge room onto the patio and looked down on the wide street for the sources of the noise. There were very few vehicles, but the few that were passing through were old and extremely noisy. From cross the road, inside a building, came the hammering and drilling. In the street below my patio, nothing interesting was happening, just people idling their engines while shouting to each other over the noise. That first morning in Havana I was reminded of Bali. The first casualty in poor countries' rush toward development is silence, and I suspect every other aspect of the natural environment follows next.

I had landed late and gone to bed without dinner. Now very hungry, I called down to my host to ask for breakfast. I made a list of essentials for the day: to find cambio or ATM, an Internet card, drinking water, and contact local friends. Dressing, I was conscious of trying to fit in and not be a target for harassment or theft. I was feeling out of sorts and realised it was the jetlag... just have to roll with it. It was a long wait for breakfast but it was satisfying when it did arrive: fresh white soft bread rolls with plain salty cheese, a thin salty omelette and a colourful fruit platter of guava, papaya, pineapple, grapefruit, cut into floral shapes. After breakfast I asked my host a few questions about how to get around town and do my errands. I was ready to go out, when someone called to the door, asking for me. Lou was ready to take me for a tour around town.

Havana Vieja with lovely Lou

Lou is a childhood friend of Liz, a Cuban flautist who I met in Europe. Introduced online, Lou and I had exchanged a few emails, but made no plan to meet. So I was surprised and delighted to see her: strikingly beautiful and slender, with smokey eye make up and pearl earrings. She has ivory skin and large dark eyes. Her wide nose and full lips suggest Afro-European roots. A long, unnaturally straight curtain of neat dark hair caresses her shoulders.Lou was dressed with conservative elegance: a navy blue blouse, tight jeans, matching sandals. Her timing was impeccable. I greeted her with thanks and a kiss and we got acquainted in Spanish.

"Luckily I didn't have to work today,” she said.

“How lucky am I!” I thought, smiling.

Lou suggested a tour of the old city, and along the way we would pick up whatever I needed. She helped me learn essential Havana skills that would've been intimidating and confusing alone: how to take a collective taxi from St Lazaro, pay the correct money, get off in the right place, navigate wide streets and plazas, find a bank, get an internet card, etc.

The collective taxi was quite an experience: riding shoulder to shoulder and thigh to thigh with random men and women in wide vintage leather car seats, in roaring, smoky traffic. Seat belts? Ha! Four wheels and a loud engine are the only requirements for taxi collectivo. The stink of petrol within and without lines your nostrils. Not exactly comfortable, but quick and very cheap.

We got out of the taxi collectivo at Parque de Fraternidad, near a replica of the White House. Lou filled me in on local history as we passed various landmarks. Apart from the grandest edifices, most of the buildings are dilapidated. Decay can look pretty in photographs... but the steady stream of hollow-eyed, dirty ruins and people living in decaying buildings is depressing. There is a desperate lack of trees on most Havana streets. There are some nice parks and plazas but most of them are not tranquil because of the surrounding traffic.

Lou said that tourists are a target for harassment because they are expected to have money, but that walking with a local I would receive more respect. One guy did try to push products into my hands but we just ignored him and turned away. A few men harassed us, refusing make way and commenting appreciatively on our appearance as we slipped past them on the narrow sidewalk, "The parade of princesses."

As we crossed a road, a bus stopped at the red light honked loudly, probably a comment on my pretty companion. The horns are super-powered in their loudness. I remarked on the general noise level, shocking to someone from a different culture. Lou had heard this from other tourists – stressed by the very noisy vehicles and the way people talk so loudly they shout. "It seems aggressive, but it's just confidence. It's harmless." she said.

We reached the harbour, where a cruise liner was docked, and crossed a beautiful square into a more touristy, well-maintained part of the city... the part with the UNESCO World Heritage listing. Passing by a lovely sandstone hotel called Casa de los Frailes, Lou stopped to greet a group of men standing in the doorway. Lou is a clarinettist. With these musicians she entertained tourists in fine hotels. While she talked, I stood and waited next to an abstract sculpture of a Franciscan monk, guarding the door like a bronze-robed ghost. Then we went to the bank and Lou waited patiently with me until I got my money sorted.

After banking, I treated Lou to lunch in a restaurant of her choosing: a 1950s American style diner, with live Cuban music. It was a colourful place with staff in vintage uniforms and a noisy, touristy vibe. This was a nice moment to share with my new friend, although it wasn't my idea of a good restaurant. I’m not a fan of deep-fried American food, breaded meats, burgers etc. It was irritating to find a woman in the bathroom looking for tips, as well as the musicians and the waitstaff.

Sitting in the diner, I expressed surprise at Cuba’s nostalgia for 1950’s American culture, despite decades of frosty relations with American governments.

“I always think of Cuba as the country that stood up to America.” I said.

Later, I learned that this Americanisation of Cuba transpired during 50 years of colonial domination by the USA. American 1950’s car culture has ruined Havana, bringing choking smog, noise and urban sprawl. Having reproduced the great American transport mistake, Cuba appears to be blindly continuing down the dead-end street of car culture. The inter-city rail network is in such a state of disrepair and unreliability that it’s effectively falling into disuse. Havana does have a bus service – very uncomfortable and inadequate judging by the sardine-like status of the passengers crammed into decrepit vehicles. Still, the Cuban people are resourceful – their taxi collectivo culture is an entreprenurial and efficient solution to the transport challenges of the sprawling city.

We sat on the sea wall and talked over the rumble of old engines and crashing waves. I wanted to learn how to pass for a local. With caramel skin and salt-n-pepper Afro hair, I’m used to standing out in most placed I’ve lived and worked. It would be nice to fit in for a change, in this country where the people are every shade of Afro brown.

Lou sees a lot of tourists in her job as the hotel musician, so she had good advice. I knew my hiking sandals were completely wrong, but I had forgotten to pack my pretty ones. Besides strappy sandals, many Cuban women wear trainers. My second mistake: wearing floral short shorts... just like a tourist. Even with a fine 25° day like this, “Cubanas wear jeans and a blouse or a dress,” said Lou. “If they wear shorts, almost always denim shorts.”

Sure enough the Cuban women lounging on the seawall wore mostly denim or pastel jeans often ripped, always skintight. The global American fashion staple, denim is worn like a uniform by Cuban men and women. From me this would be very uncomfortable, but I wouldn't mind to wear a dress.

“I’ll have to buy one locally,” I thought, “as my swing dance dresses would stand out a mile here.”

“How lucky am I!” I thought, smiling.

Lou suggested a tour of the old city, and along the way we would pick up whatever I needed. She helped me learn essential Havana skills that would've been intimidating and confusing alone: how to take a collective taxi from St Lazaro, pay the correct money, get off in the right place, navigate wide streets and plazas, find a bank, get an internet card, etc.

The collective taxi was quite an experience: riding shoulder to shoulder and thigh to thigh with random men and women in wide vintage leather car seats, in roaring, smoky traffic. Seat belts? Ha! Four wheels and a loud engine are the only requirements for taxi collectivo. The stink of petrol within and without lines your nostrils. Not exactly comfortable, but quick and very cheap.

We got out of the taxi collectivo at Parque de Fraternidad, near a replica of the White House. Lou filled me in on local history as we passed various landmarks. Apart from the grandest edifices, most of the buildings are dilapidated. Decay can look pretty in photographs... but the steady stream of hollow-eyed, dirty ruins and people living in decaying buildings is depressing. There is a desperate lack of trees on most Havana streets. There are some nice parks and plazas but most of them are not tranquil because of the surrounding traffic.

Lou said that tourists are a target for harassment because they are expected to have money, but that walking with a local I would receive more respect. One guy did try to push products into my hands but we just ignored him and turned away. A few men harassed us, refusing make way and commenting appreciatively on our appearance as we slipped past them on the narrow sidewalk, "The parade of princesses."

As we crossed a road, a bus stopped at the red light honked loudly, probably a comment on my pretty companion. The horns are super-powered in their loudness. I remarked on the general noise level, shocking to someone from a different culture. Lou had heard this from other tourists – stressed by the very noisy vehicles and the way people talk so loudly they shout. "It seems aggressive, but it's just confidence. It's harmless." she said.

We reached the harbour, where a cruise liner was docked, and crossed a beautiful square into a more touristy, well-maintained part of the city... the part with the UNESCO World Heritage listing. Passing by a lovely sandstone hotel called Casa de los Frailes, Lou stopped to greet a group of men standing in the doorway. Lou is a clarinettist. With these musicians she entertained tourists in fine hotels. While she talked, I stood and waited next to an abstract sculpture of a Franciscan monk, guarding the door like a bronze-robed ghost. Then we went to the bank and Lou waited patiently with me until I got my money sorted.

After banking, I treated Lou to lunch in a restaurant of her choosing: a 1950s American style diner, with live Cuban music. It was a colourful place with staff in vintage uniforms and a noisy, touristy vibe. This was a nice moment to share with my new friend, although it wasn't my idea of a good restaurant. I’m not a fan of deep-fried American food, breaded meats, burgers etc. It was irritating to find a woman in the bathroom looking for tips, as well as the musicians and the waitstaff.

Sitting in the diner, I expressed surprise at Cuba’s nostalgia for 1950’s American culture, despite decades of frosty relations with American governments.

“I always think of Cuba as the country that stood up to America.” I said.

Later, I learned that this Americanisation of Cuba transpired during 50 years of colonial domination by the USA. American 1950’s car culture has ruined Havana, bringing choking smog, noise and urban sprawl. Having reproduced the great American transport mistake, Cuba appears to be blindly continuing down the dead-end street of car culture. The inter-city rail network is in such a state of disrepair and unreliability that it’s effectively falling into disuse. Havana does have a bus service – very uncomfortable and inadequate judging by the sardine-like status of the passengers crammed into decrepit vehicles. Still, the Cuban people are resourceful – their taxi collectivo culture is an entreprenurial and efficient solution to the transport challenges of the sprawling city.

Malecon

After lunch and more sightseeing around the old town, we jumped in a taxi collectivo again. Our next stop was at the famous seafront – Malecon. It was disappointing: a long highway with no recreational amenity except for a wide sea wall and wide pavement. Its just as well the traffic is sparse, as there is no pedestrian crossing. There is not a tree, not a blade of grass, nowhere to take refuge from the grey ugliness of six lanes of concrete motorway. Across the road from us was cliff, about 3.5 metres tall, surmounted by the famous Hotel Nacional, with its garden overlooking the sea. However, from street level, it’s all you can do to sit on the concrete wall and look down at the jagged sandstone or out at the ocean. The turquoise blue is beautiful, but it’s rough water and apparently swimming is forbidden.We sat on the sea wall and talked over the rumble of old engines and crashing waves. I wanted to learn how to pass for a local. With caramel skin and salt-n-pepper Afro hair, I’m used to standing out in most placed I’ve lived and worked. It would be nice to fit in for a change, in this country where the people are every shade of Afro brown.

Lou sees a lot of tourists in her job as the hotel musician, so she had good advice. I knew my hiking sandals were completely wrong, but I had forgotten to pack my pretty ones. Besides strappy sandals, many Cuban women wear trainers. My second mistake: wearing floral short shorts... just like a tourist. Even with a fine 25° day like this, “Cubanas wear jeans and a blouse or a dress,” said Lou. “If they wear shorts, almost always denim shorts.”

Sure enough the Cuban women lounging on the seawall wore mostly denim or pastel jeans often ripped, always skintight. The global American fashion staple, denim is worn like a uniform by Cuban men and women. From me this would be very uncomfortable, but I wouldn't mind to wear a dress.

“I’ll have to buy one locally,” I thought, “as my swing dance dresses would stand out a mile here.”

“My rucksack is also quite touristy?” I asked.

“Yes,” Lou said, “See how they wear a handbag bag slung across their shoulder?”

“And what about my hair?”

“The Afro is okay,” said Lou, “people do wear Afros here.”

After learning the dress code, I enjoyed reading people’s fashion as I walked the streets.

Despite Lou’s wonderful welcome and her tour of the nicest parts of the city, the feeling that I got as I walked back from Malecon was sadness – disappointment maybe. Despite hearing mixed reviews about Cuba, I had expected that I would like it. Havana seemed to me an urban dystopia, its people trapped between American imperialism, corrupt communism and missed opportunities. If the municipality planted trees, laid bike paths and adopted a better public transport culture, they could have a beautiful city. There’s no sign of any such vision for the future. As Lou said,

For my first week in Habana, I stayed in Basarrate – a minor, residential street but quite broad. Located near the University between Havana Vieja and Vedado, it is lined with 1930s pastiche colonial terrace town house in faded, cracked and mouldy pastel colours. Many of them are fronted with tall wrought iron gates or shutters. Most of these homes look quite large and comfortable, whenever I glimpse an interior from the balcony or the street. The barrio is clean, except for the local park, where a grand old tree stands in a pile of garbage.

Basarrate is like a time warp, naked for lack of cars, shops, signage or advertising. Down the middle of the road, occasionally a hawker will pass, advertising in a singsong voice products that are usually absent from supermarkets. A man pushes a wheelbarrow of greens. Later, with strings of garlic and onion around his neck, a man sells the fragrant bulbs from the basket of his bike. “Flores!” calls the flower-seller, as he pedals slowly around the corner. From their balconies, women pause from their chores to take some sun or look down on the street. One or two men are working on a car engine on almost every side street. Keeping these old cars running is a national pastime. It would be quiet except for the car horns, the roar of old engines, the singing cries of the hawkers and a very loud conversations always happening in doorways and street corners. This noise starts about 07:00 and continues to about 22:00 hours. Cuba has a loud culture.

For a few hours after dark, in almost every doorway, young and old people sit in pairs staring at mobile phones, using a local private Wi-Fi network paid by the hour. I tried to use it, but my money was wasted – I did not get even one minute of connection after paying for an hour. From then on, I stuck with the government internet service. It's paid by the hour and only available in parks, plazas and fancy hotels.

I took a street parallel to mine, for a change. Doorways opened onto family homes and a living-room nail salon. At one wide doorway, there was small queue of people standing by a counter. The store was poorly lit and shadowy, selling mysterious goods. It was unlike any store I had ever seen, as I could not tell what they were selling. There was no signage and colourless packaging or none at all. I passed by the local park with its garbage pile and small groups of people. As I approached the main road, St. Lazaro, I saw a military police truck and officers standing idly by. Nobody troubled me.

I got a friendly reception in the restaurant, from two men and a woman staffing the empty bar. I asked the young waitress about the barrio. She said “Don't worry, nothing happens here because of the police presence.”

I told them that I was getting takeaway food because I was afraid to walk home after dark. They reassured me. A friendly, but loud and annoying man at the bar took it upon himself to assure me that I can walk around any time, even four in the morning.

“Easy for you to say.” I thought.

“Nobody will rob, rape, assault or kidnap you. Cuba is safe,” he said, “you're going to love it.”

While I sat at the bar drinking sangria and waiting for my food, the loud man asked dumb questions. "Why are you traveling alone? Wouldn't you have more fun with friends?"

He would not take no for an answer when I refused to give him my age. After these tedious attempts at conversation and saying he liked my face, he gave me his phone number and offered to take me dancing.

“I won’t charge you anything,” he said. It was a nice offer if he was not so annoying.

After my first few nervous days, I found that Cuba’s reputation as one of the safest Central American destinations is deserved. Firearms trafficking out of the USA has brought a scourge of lawlessness and untimely deaths to many parts of the Americas, including my mother’s island of Barbados. If Cuba has escaped the American disease of easy access to guns, it is probably a gift of the embargo. Also, although much of the infrastructure is crumbling and products are scarce, it seems that Cubans’ basic needs are met, because they are not desperados. While many people are poor, there’s a calmness or resignation about them.

For locals, smart phones and internet are expensive. Not everyone has a phone, especially in the countryside. This meant that effectively, for social purposes within Cuba, there was next to no internet. I could not rely on it to find local dance communities or events. If you send a message to a Cuban today, they may see read it tomorrow, or in a week, or two. You learn to rely on neighbourliness, visits, land lines, promises and being punctual ... like the old days. Not an entirely bad thing, I found. In some ways, the human connections from Cuba felt deeper and more real – perhaps because we had fewer distractions and couldn't rely on virtual ties.

Cuba is a land of many contrasts and contradictions: Americanised, but unAmerican; polluted motor city and pristine tropical paradise; famous for a revolution... and perhaps overdue for another one? Havana was a culture shock, but I had faith. The friendships and curiosity about Cuban people and culture that had brought me to the island would make it all worthwhile.

“Yes,” Lou said, “See how they wear a handbag bag slung across their shoulder?”

“And what about my hair?”

“The Afro is okay,” said Lou, “people do wear Afros here.”

After learning the dress code, I enjoyed reading people’s fashion as I walked the streets.

Despite Lou’s wonderful welcome and her tour of the nicest parts of the city, the feeling that I got as I walked back from Malecon was sadness – disappointment maybe. Despite hearing mixed reviews about Cuba, I had expected that I would like it. Havana seemed to me an urban dystopia, its people trapped between American imperialism, corrupt communism and missed opportunities. If the municipality planted trees, laid bike paths and adopted a better public transport culture, they could have a beautiful city. There’s no sign of any such vision for the future. As Lou said,

As long as this regime remains in power, nothing will change.

La Calle by day

For my first week in Habana, I stayed in Basarrate – a minor, residential street but quite broad. Located near the University between Havana Vieja and Vedado, it is lined with 1930s pastiche colonial terrace town house in faded, cracked and mouldy pastel colours. Many of them are fronted with tall wrought iron gates or shutters. Most of these homes look quite large and comfortable, whenever I glimpse an interior from the balcony or the street. The barrio is clean, except for the local park, where a grand old tree stands in a pile of garbage.

Basarrate is like a time warp, naked for lack of cars, shops, signage or advertising. Down the middle of the road, occasionally a hawker will pass, advertising in a singsong voice products that are usually absent from supermarkets. A man pushes a wheelbarrow of greens. Later, with strings of garlic and onion around his neck, a man sells the fragrant bulbs from the basket of his bike. “Flores!” calls the flower-seller, as he pedals slowly around the corner. From their balconies, women pause from their chores to take some sun or look down on the street. One or two men are working on a car engine on almost every side street. Keeping these old cars running is a national pastime. It would be quiet except for the car horns, the roar of old engines, the singing cries of the hawkers and a very loud conversations always happening in doorways and street corners. This noise starts about 07:00 and continues to about 22:00 hours. Cuba has a loud culture.

For a few hours after dark, in almost every doorway, young and old people sit in pairs staring at mobile phones, using a local private Wi-Fi network paid by the hour. I tried to use it, but my money was wasted – I did not get even one minute of connection after paying for an hour. From then on, I stuck with the government internet service. It's paid by the hour and only available in parks, plazas and fancy hotels.

La Calle after sunset

Walking in the day, Lou and myself had experienced ordinary sexual harrassment, so ordinary macho violence was a potential threat too. Lou had advised me to take a taxi door-to-door at night, but later I understood that this was only necessary after the local families and restaurants close their doors. On my first evening alone in Havana, I was nervous about walking the streets, after sunset. So I changed into long pants and trainers and set out for Casa del Taco, four blocks from my B&B, an hour before sunset.I took a street parallel to mine, for a change. Doorways opened onto family homes and a living-room nail salon. At one wide doorway, there was small queue of people standing by a counter. The store was poorly lit and shadowy, selling mysterious goods. It was unlike any store I had ever seen, as I could not tell what they were selling. There was no signage and colourless packaging or none at all. I passed by the local park with its garbage pile and small groups of people. As I approached the main road, St. Lazaro, I saw a military police truck and officers standing idly by. Nobody troubled me.

I got a friendly reception in the restaurant, from two men and a woman staffing the empty bar. I asked the young waitress about the barrio. She said “Don't worry, nothing happens here because of the police presence.”

I told them that I was getting takeaway food because I was afraid to walk home after dark. They reassured me. A friendly, but loud and annoying man at the bar took it upon himself to assure me that I can walk around any time, even four in the morning.

“Easy for you to say.” I thought.

“Nobody will rob, rape, assault or kidnap you. Cuba is safe,” he said, “you're going to love it.”

While I sat at the bar drinking sangria and waiting for my food, the loud man asked dumb questions. "Why are you traveling alone? Wouldn't you have more fun with friends?"

He would not take no for an answer when I refused to give him my age. After these tedious attempts at conversation and saying he liked my face, he gave me his phone number and offered to take me dancing.

“I won’t charge you anything,” he said. It was a nice offer if he was not so annoying.

After my first few nervous days, I found that Cuba’s reputation as one of the safest Central American destinations is deserved. Firearms trafficking out of the USA has brought a scourge of lawlessness and untimely deaths to many parts of the Americas, including my mother’s island of Barbados. If Cuba has escaped the American disease of easy access to guns, it is probably a gift of the embargo. Also, although much of the infrastructure is crumbling and products are scarce, it seems that Cubans’ basic needs are met, because they are not desperados. While many people are poor, there’s a calmness or resignation about them.

For locals, smart phones and internet are expensive. Not everyone has a phone, especially in the countryside. This meant that effectively, for social purposes within Cuba, there was next to no internet. I could not rely on it to find local dance communities or events. If you send a message to a Cuban today, they may see read it tomorrow, or in a week, or two. You learn to rely on neighbourliness, visits, land lines, promises and being punctual ... like the old days. Not an entirely bad thing, I found. In some ways, the human connections from Cuba felt deeper and more real – perhaps because we had fewer distractions and couldn't rely on virtual ties.

Cuba is a land of many contrasts and contradictions: Americanised, but unAmerican; polluted motor city and pristine tropical paradise; famous for a revolution... and perhaps overdue for another one? Havana was a culture shock, but I had faith. The friendships and curiosity about Cuban people and culture that had brought me to the island would make it all worthwhile.

Comments